- Say No

Wild Caught

Region:

Commonwealth waters

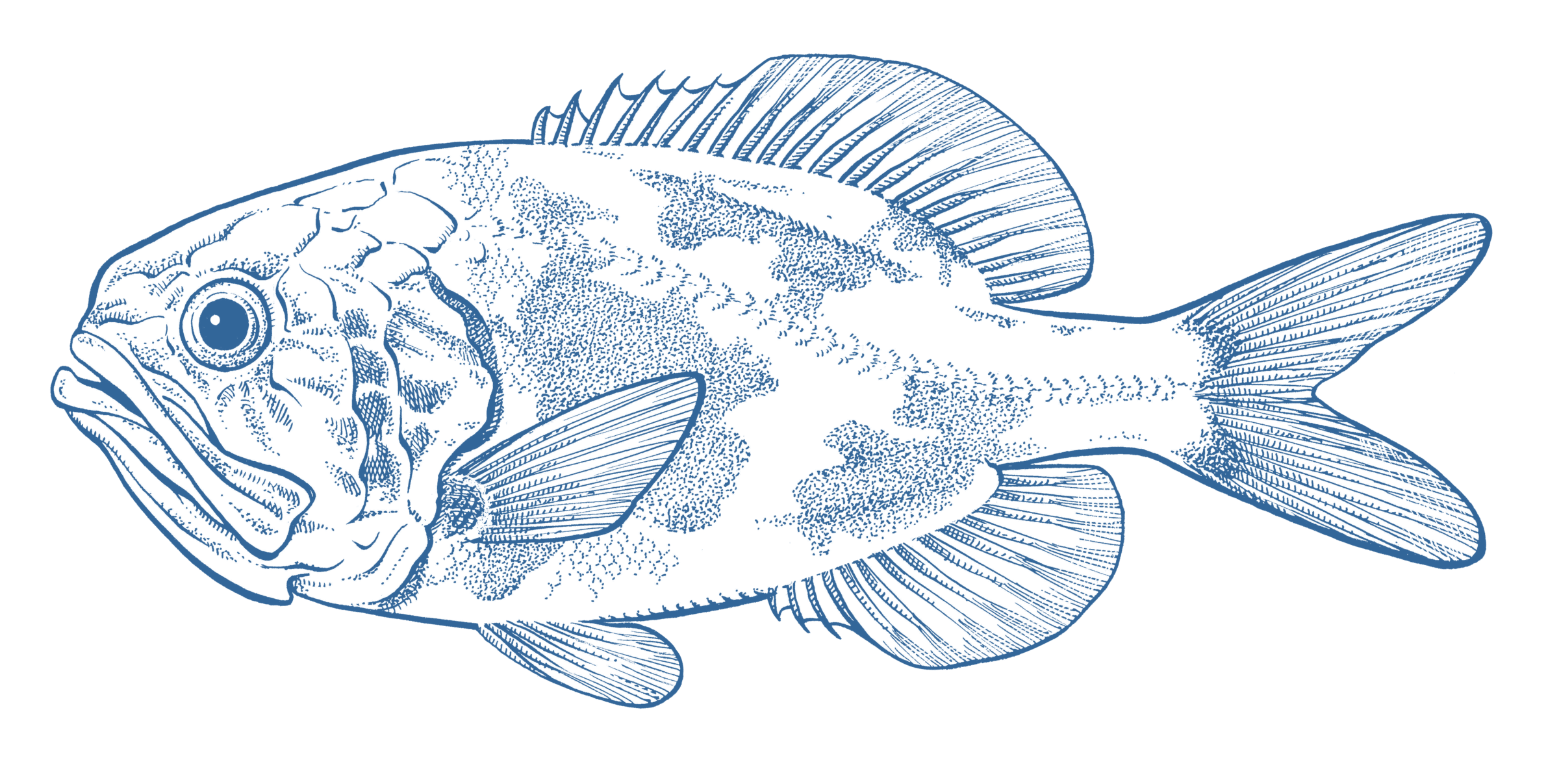

- Orange roughy live for up to 250 years and inhabit deep ocean waters. The biology of this species (late to reproduce and exceptionally long lived) makes them particularly vulnerable to fishing, as they are unable to reproduce quickly enough to replenish their numbers.

- Intense fishing pressure in the 1980s and 90s led to severe declines and the species is now listed as protected under Australian environmental law. Targeted fishing is permitted in some areas in Australia. Some rebuilding of orange roughy in one management zone has occurred, though the fishery is not predicted to reach truly sustainable levels until after 2070.

- An increasing proportion of the orange roughy catch has been taken from large New Zealand-owned factory freezer trawlers, which visit during Winter to fish spawning aggregations that form across the top of undersea mountains east of Tasmania. The fishery catches some threatened species such as Australian fur seals, shortfin mako sharks and seabirds, although industry has been proactive in trying to reduce mortalities of these vulnerable species.

- The fishery catches some threatened species such as Australian fur seals, deepwater sharks and seabirds, although industry has been proactive in trying to reduce mortalities of these vulnerable species.

- The fishery operates around a major global ocean heating hotspot but does not explicitly account for climate change when setting future catch limits. Significant research in this area is welcome, but is overdue.

- Comprehensive research has been undertaken into the ecosystem impacts of the fishery but not adopted by managers. The research demonstrates that the fishery is likely Australia’s most destructive, causing damage to deep sea coral reefs that lasts decades and could take centuries to recover.

Commonwealth Southern and Eastern Scalefish and Shark Fishery (Commonwealth Trawl Sector) (1,847t in 2021/22)

Orange roughy is a deepwater demersal predatory fish found throughout southern hemisphere ocean basins at depths of between 700-1300m. The species is extraordinarily long-lived, with individuals aged at up to 250 years old.

They are caught in Australia using bottom otter trawl fishing methods in the Commonwealth SESSF Commonwealth Trawl Sector, primarily around the crest of seamounts where they form spawning aggregations during winter months.

Orange roughy has been so overfished in Australia, that it is now listed as an endangered species; categorised as ‘conservation dependent’ under Commonwealth environmental legislation. This still permits fishing and sale of this protected species.

The number of orange roughy populations fished in Australia is uncertain, and the fishery is managed as nine management units.

Only one of these management units off eastern Tasmania is known to have recovered from past overfishing to a level where targeted fishing is legally permitted, though is not expected to return to a truly sustainable target level until some time after 2070. Despite a recent stock assessment revising the estimated population size downwards, future catches have been set (at industry’s request) at levels almost 50% higher than the scientific recommendation. This does not signify responsible management.

The fishery has made significant progress in reducing protected seabird bycatch, though fur seal bycatch is potentially increasing. Seal Excluder Devices (SEDs), which act as escape hatches for seals that enter trawl nets, are mandatory. All trawl boats must have a seabird management plan in place to guide how each boat aims to reduce interactions with seabirds while actively fishing. Many of the solutions to seabird interactions have been fishing industry-led innovations and are proving highly successful in reducing these impacts. Orange roughy fishing has relatively little bycatch, compared to shallow-water trawl fishing.

No Australian fishery has pushed more of its former target and secondary species onto our endangered species lists, and there is no evidence of recovery for most of these species. Special rebuilding strategies that allow these species to be caught and sold while holding this protected status are largely failing to deliver sufficient if any actual rebuilding.

Without major reform, AMCS expects more species caught by the SESSF to be placed on the Australian endangered species list than will recover off it in the foreseeable future.

The SESSF operates around a global ocean heating hotspot, warming at almost four times the global average. While serious climate impacts have been attributed to declining SESSF fish stocks for around a decade, there is still no explicit consideration of climate impacts when setting future catch limits. Significant research is underway in this area, which is welcome but overdue.

Most orange roughy fishing occurs on winter-time spawning aggregations that form at the peaks of underwater seamounts. These seamount peaks were (prior to fishing) covered in ecologically complex and extremely vulnerable deep sea corals. Australian scientists recently conducted one of the most comprehensive observational studies of the impacts of orange roughy fishing on seamount corals across the past and present Tasmanian fishing grounds. The research found these coral reefs almost entirely destroyed, and showing almost no recovery even 20 years after a seamount had been protected from fishing. Recovery of these coral reefs is likely to take decades to centuries to occur. Given this, orange roughy fishing is likely Australia’s most destructive fishery. Despite this, no changes to the Australian fishery’s operation have been made in the four years since this research was conducted, and ecological risk management is still done based on information from a period when the fishery was largely banned altogether (so could not well describe the actual impacts of fishing).

There has been considerable investment in scientific research around the ecosystem and habitat impacts of the fishery, but this has not been supported by sufficient implementation of meaningful protections from fishing and climate-related impacts in the fishery, which have both been severe. Commonwealth waters marine parks are in place throughout the fishery but were designed primarily to avoid key fishing grounds, so confer little benefit. All the key fishing grounds where targeted orange roughy fishing is legally permissible are open to fishing, and fishery managers have recently allowed ‘research fishing’ in multiple areas otherwise closed to deepwater trawling, in the hopes of collecting evidence to support reopening the fishery further.