- Say No

Wild Caught

Region:

QLD

- Barramundi are caught in commercial gillnet fisheries in coastal waters, estuaries and river mouths in QLD, WA and NT waters.

- There are several populations or stocks of barramundi that are fished around northeastern QLD and the Gulf of Carpentaria. Most stocks are healthy but there are some concerning signs in some stocks.

- Gillnets catching barramundi also catch significant numbers of protected and vulnerable wildlife as bycatch, including turtles, dugongs and hammerhead sharks.

- The fishery observer program in QLD was cancelled in 2012, meaning there is no independent record of the impact of the fishery on threatened species. Observation of the fishery is considered essential to the management of a sustainable fishery.

- QLD East Coast Inshore Fishery and Gulf of Carpentaria Inshore Fishery (663t in 2021, 626t in 2020)

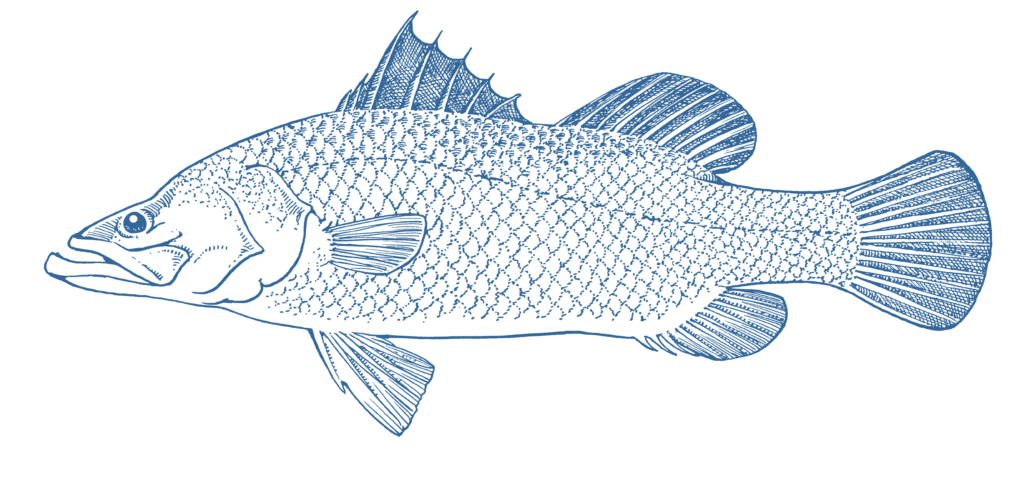

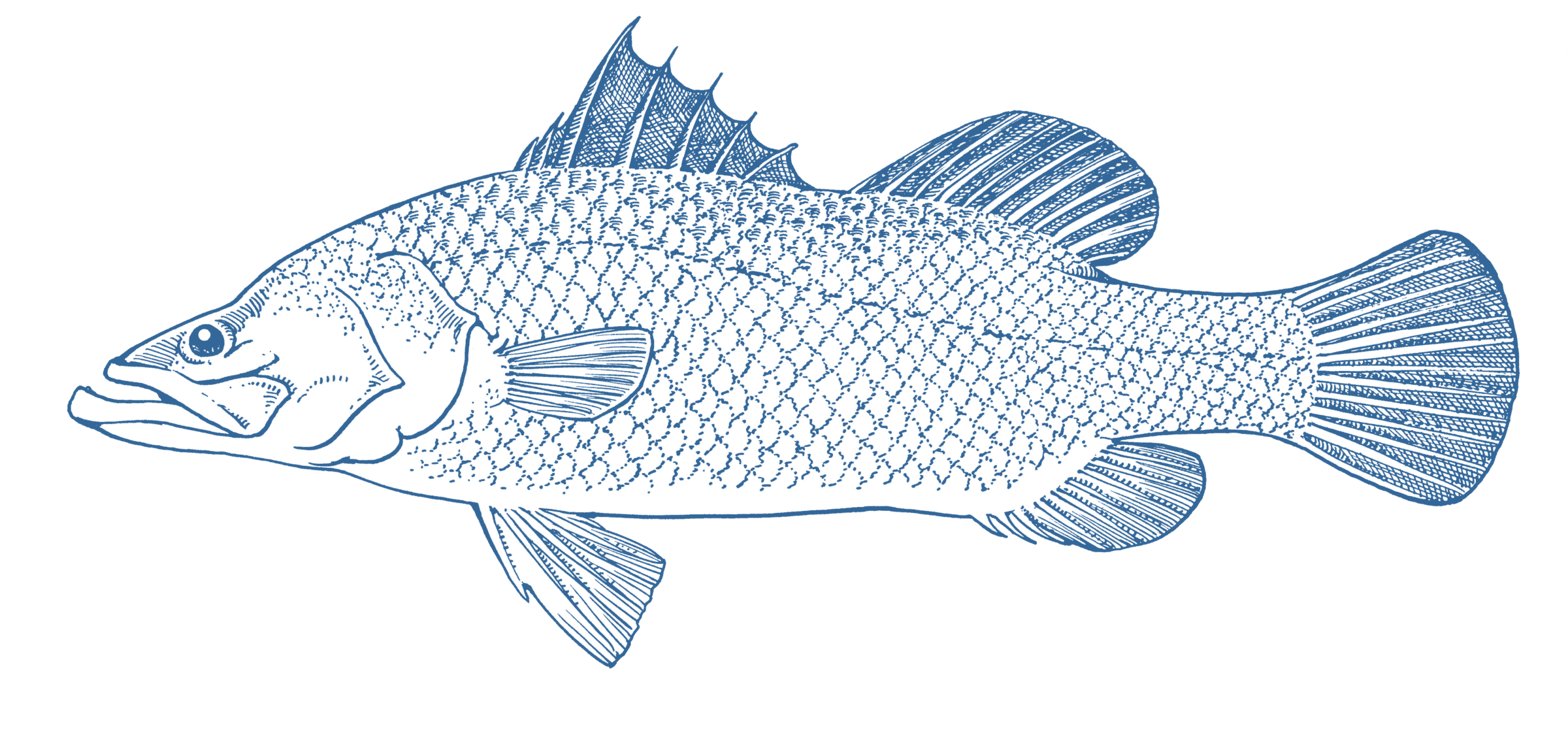

Barramundi is caught mainly using gillnets in two Queensland-managed fisheries operating off the eastern and Gulf coasts.

A program of scientific assessment and modernised management arrangements for the fishery has recently been introduced, which is welcome. There are several populations or stocks of barramundi that are fished around northeastern QLD and the Gulf of Carpentaria. The scientific assessment shows that stocks are broadly healthy but there are some concerning signs in some stocks, including the major Gulf of Carpentaria stock, where egg production appears low. This may have consequences for the future sustainability of the fishery.

In both fisheries a number of threatened species are caught as bycatch, including green, loggerhead, and flatback turtles, inshore dolphins, dugongs, sawfish and a number of shark species, including hammerhead sharks. Even low levels of snubfin and humpback dolphin deaths will have a significant impact on their populations in QLD, and it is highly likely that fishing activity is resulting in the decline of populations in some areas.

In the Gulf of Carpentaria fishery a key secondary species that is caught in barramundi nets, king threadfin, has been dangerously overfished.

Fisheries managers in QLD have also reported inconsistencies between fisheries logbook records and information from independent observers, including differences between the number, rate and type of protected species interactions. There is a high probability that protected species bycatch is higher than reported.

Sectors of both fisheries also target some shark species, despite a lack of information on their stock status. There is limited information on much of the basic biology of many of the targeted species, e.g. their age at maturity, frequency of reproduction and number of young. This lack of knowledge is particularly concerning as shark species are generally long-lived, slow to mature and produce few young, making them highly vulnerable to population depletion as a result of fishing activity. Sharks are also apex predators that are essential to maintaining healthy marine food webs.

Independent fishery observer programs are an important method of verifying protected species interactions. Unfortunately the QLD Government closed the observer program for all QLD managed fisheries in 2012. Since that time there remains no independent on-vessel monitoring of the fishery’s impact, which is unacceptable for fisheries operating in the ecologically sensitive regions of the Great Barrier Reef and the Gulf of Carpentaria. In addition, for fisheries that interact with threatened species, there is no record of actual protected species interactions over time, the ecological impacts of the fishery cannot be measured or managed but these these fisheries are considered to pose a high risk to a range of threatened and vulnerable species.

While significant and laudable management reforms have been implemented in the east coast fishery; there has been insufficient action at time of writing to deliver improved environmental outcomes, particularly for threatened and protected species. Rankings in this fishery may be expected to improve in future. The Gulf of Carpentaria coast fishery continues to feature rudimentary and retrograde management arrangements and poses a significant threat to both target and bycatch species.