- Eat Less

Wild Caught

Region:

Commonwealth waters

- Blue grenadier are caught using bottom and midwater trawls in a Commonwealth managed fishery in Australia.

- Blue grenadier populations are in a healthy condition, though the effects of a major recent increase in fishing intensity require careful monitoring.

- The fishery catches some threatened species such as Australian fur seals, shortfin mako sharks and seabirds, although industry has been proactive in trying to reduce mortalities of these vulnerable species. There are some concerns around bycatch of seriously overfished (and now endangered) eastern gemfish and school shark.

- There is an adequate level of independent scrutiny of blue grenadier fishing via fishery observers, ensuring reliable data on the fishery’s impacts on bycatch species is being collected.

- Most blue grenadier catch comes from large New Zealand-owned factory freezer trawlers, which visit during Winter to fish spawning aggregations around undersea canyons west of Tasmania.

- The fishery operates around a major global ocean heating hotspot but does not explicitly account for climate change when setting future catch limits. Significant research is welcome in this area but is overdue.

- There has been significant research into the ecosystem impacts of the fishery, but marine park protections are seriously inadequate and if improved could significantly increase the resilience of target and bycatch species, and vulnerable seafloor habitats.

- Commonwealth Southern and Eastern Scalefish and Shark Fishery (Commonwealth Trawl Sector) (10,958t in 2021/22)

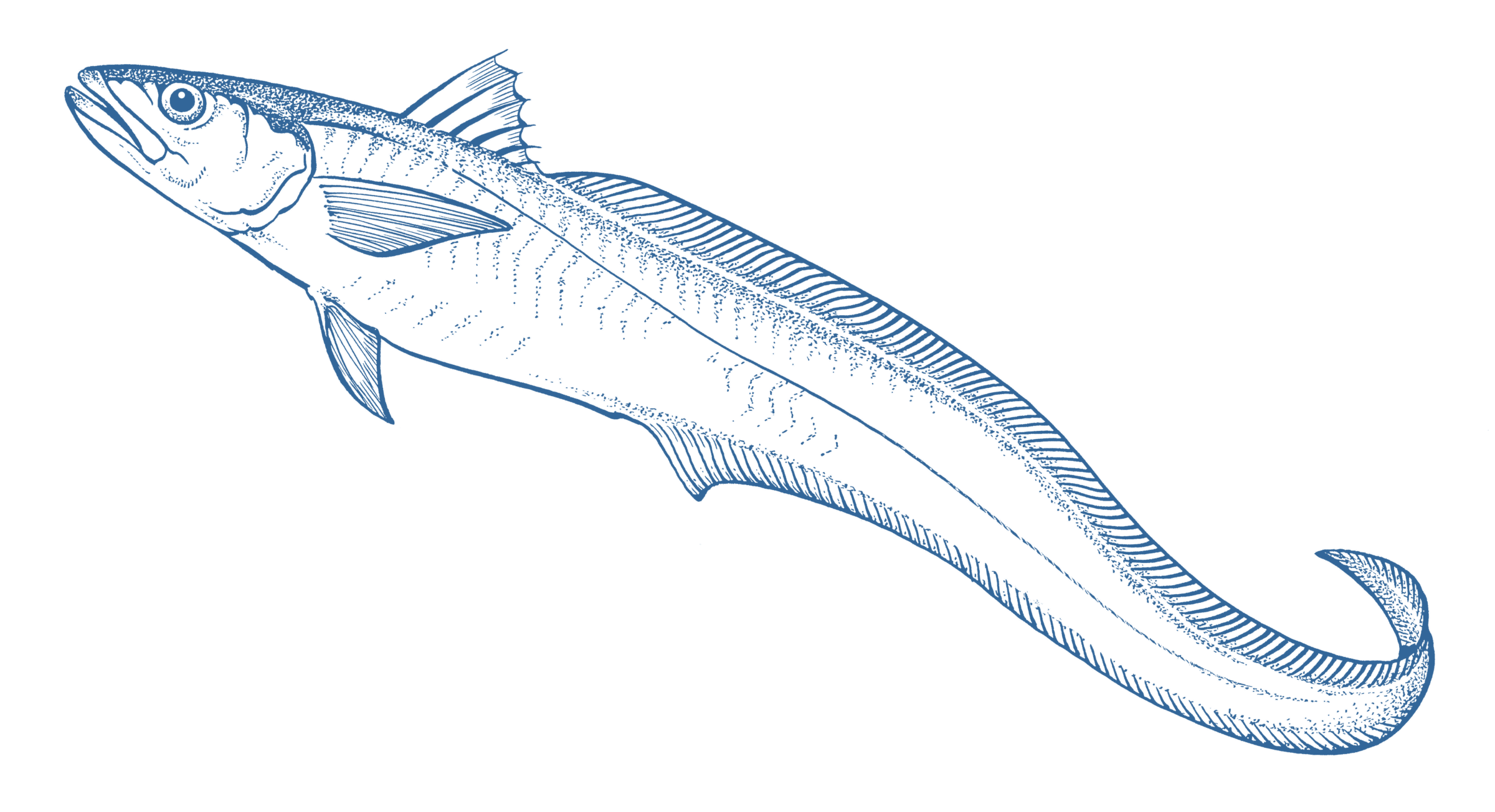

Blue Grenadier (also known as Hoki) are a bentho-pelagic predatory finfish found throughout Australian, New Zealand and wider southwestern Pacific Ocean waters. They usually live on or near the bottom in depths from 400-1000m, but may occasionally move up into mid-waters. Large adult fish generally occur deeper than 400 m, while juveniles may be found in shallower water, more commonly found in large estuaries and bays, and may even enter freshwaters.

Blue Grenadier are caught using bottom and midwater trawl in Australia in the Commonwealth-managed Southern and Eastern Scalefish and Shark Fishery (SESSF), which is Australia’s largest source of locally caught finfish for the domestic market.

The fishery has made significant progress in reducing protected seabird bycatch, though fur seal bycatch is potentially increasing. Seal Excluder Devices (SEDs), which act as escape hatches for seals that enter trawl nets, are mandatory. All trawl boats must have a seabird management plan in place to guide how each boat aims to reduce interactions with seabirds while actively fishing. Many of the solutions to seabird interactions have been fishing industry-led innovations and are proving highly successful in reducing these impacts.

Most concerning is bycatch of fishes – including eastern gemfish and school shark – which used to be primary or secondary target species of the fishery, that have been so severely overfished by the SESSF that they are now on the Australian Threatened, Endangered or Protected Species lists.

No Australian fishery has pushed more of its former target and secondary species onto our endangered species lists, and there is no evidence of recovery for most of these species. Special rebuilding strategies that allow these species to be caught and sold while holding this protected status are largely failing to deliver sufficient if any actual rebuilding.The SESSF blue grenadier fishery has an adequate level of independent observer coverage to support collection of reliable information on bycatch species, which is welcome.

The SESSF operates around a global ocean heating hotspot, warming at almost four times the global average. While serious climate impacts have been attributed to declining SESSF fish stocks for around a decade, there is still no explicit consideration of climate impacts when setting future catch limits. Significant research is underway in this area, which is welcome but overdue.

There has been considerable investment in scientific research around the ecosystem and habitat impacts of the fishery, but this has not been supported by sufficient implementation of meaningful protections from fishing and climate-related impacts in the fishery, which have both been severe. Commonwealth waters marine parks are in place throughout the fishery but were designed primarily to avoid key fishing grounds, so confer little benefit. While marine parks should be a valuable and cost-effective tool for protecting vulnerable species and habitats; providing both resilience and a scientific resource to manage climate impacts; they (along with existing fishery area closures), protect almost none of the most heavily fished habitats in the fishery. Improving marine park protection will be critical to addressing and rebuilding the future sustainability of the SESSF fishery.